The global rise in inequality, particularly in advanced economies, has become one of the most pressing issues of our time (Milanovic 2016). Thomas Piketty’s work has sparked a critical conversation on the concentration of wealth, wherein an increasing share of resources is controlled by the top 1 percent, leading to growing social and economic disparities (Alvaredo et al. 2013). The discussion around inequality has shifted from whether it exists to understanding its root causes and how it shapes contemporary society (Owens 2018; Litchfield 1999). While Piketty, inspired by Marxist and Keynesian theory, and others argue that wealth taxes and state intervention are necessary solutions, many libertarians and market economists contend that excessive state involvement may itself be one of the primary drivers of inequality, particularly through distorting market competition (Piketty 2014; Stiglitz 2013; Hayek 1976; Rothbard 2000).[1]

Despite Piketty’s contribution, several gaps still remain in the literature, especially regarding the distinction between entrepreneurs who succeed through market mechanisms and those who thrive due to state intervention (Hoppe 2013; Gigauri and Damenia 2020). The current body of work has yet to fully explore the difference between naturally successful entrepreneurs, who earn their wealth through innovation and market competition, and artificially successful entrepreneurs, whose success is primarily due to political connections, government subsidies, and other forms of state support (Holcombe 1998; Foss and Klein 2012). This gap is critical to understanding inequality, as much of the current debate fails to account for how state mechanisms create an uneven playing field that rewards certain actors disproportionately (Bylund 2016b; Holcombe 2018).

In this article, I aim to fill this gap by distinguishing between natural and artificial entrepreneurs and exploring how state intervention contributes to rising inequality (Packard and Bylund 2018). By analyzing the mechanisms through which government policies—protectionist regulations, fiscal advantages, prohibitions, license requirements, quality or safety standards, price controls, quotas, subsidies, expansionary monetary policy, and so on—favor artificial entrepreneurs, I will evoke an understudied and undertheorized area in libertarian studies: that much of the wealth concentration we observe is not the result of free-market forces but rather a by-product of state-driven market distortions (Mises 1996; Rothbard 2006b).

The Relationship between Inequality and Entrepreneurship

Various economic schools of thought provide diverse perspectives on the relationship between inequality and entrepreneurship, highlighting different drivers and implications.

A Summary by Economic School of Thought

Classical economists like Adam Smith view entrepreneurship as a fundamental mechanism for economic growth, with inequalities emerging naturally from differences in talent, effort, and initial resources (Michael 2007; Aspromourgos 2014; A. Smith 1776). David Ricardo also follows this argument (Letiche 1960; Rothbard 2006a). Disparities are seen as the result of productive contributions and the efficient use of resources. However, classical thinkers give limited attention to the role of state intervention in creating distortions, focusing instead on the importance of strong institutions to protect property and enforce contracts (Klein 1998).

In contrast, the Marxist perspective sees entrepreneurship as inherently tied to the exploitation of labor within a capitalist system (Mises 2006; Böhm-Bawerk 1949). Karl Marx argues that inequalities arise from the accumulation of capital by the ruling class, which intensifies societal disparities and consolidates power (Marx and Engels 2008; Marx 1981, 1970). From this viewpoint, entrepreneurship often functions as a tool of the bourgeoisie, supported by state mechanisms that perpetuate their dominance. Similarly, Schumpeterian economics acknowledges that entrepreneurship drives “creative destruction,” leading to temporary inequalities as markets adapt to innovation. While these disparities are seen as necessary for economic dynamism, Joseph Schumpeter warns that monopolies and excessive state intervention can hinder this process, exacerbating artificial inequalities (Cheah 1990; Schumpeter 1934; Kirzner 1999).

The neoclassical school takes a more neutral stance, viewing entrepreneurship as a resource optimization process where inequalities reflect differences in productivity, risk-taking, and skill (Bianchi and Henrekson 2005; Glancey and McQuaid 2000). Entrepreneurs succeed based on their contributions to production, and disparities are considered the natural outcome of market dynamics. However, critics argue that this school underestimates the impact of state interventions like subsidies and protectionism, which distort wealth creation and amplify inequalities (Giménez Roche 2017). On the other hand, Austrian economists like Ludwig von Mises and Israel Kirzner emphasize entrepreneurship as central to market processes, where disparities are voluntary outcomes of consumer preferences and entrepreneurial action (Mises 1996; Kirzner 1973). Austrians strongly critique state-driven distortions, such as regulatory favoritism, which they argue create what I term artificial entrepreneurs and exacerbate inequities beyond what free markets would produce.

Subsequent schools integrate additional dimensions into the discussion. Keynesian economics emphasizes the role of aggregate demand in sustaining entrepreneurship, arguing that extreme inequalities limit consumption and investment, thereby hindering economic growth (Keynes 1936; Hazlitt 1959). Policies such as progressive taxation and robust public spending are seen as tools to reduce barriers and ensure a stable environment for entrepreneurial success. Building on this, institutional economics highlights the importance of transparent and inclusive institutions in shaping entrepreneurial opportunities. Failures such as corruption, weak property rights, and biased regulations are identified as key drivers of inequality, disproportionately benefiting politically connected, artificial entrepreneurs (Foss and Klein 2012).

Finally, modern approaches like development, behavioral, post-Keynesian, and ecological economics further broaden the analysis (Dabic, Cvijanović, and González-Loureiro 2011; Davis 2010). Development economists emphasize structural barriers, such as limited access to credit and education, which restrict entrepreneurial participation among marginalized groups (Sachs 2006; Robinson 2012). Behavioral economics examines how social norms and cognitive biases influence entrepreneurial behavior, with safety nets reducing fear of failure in unequal societies (Rubinstein 2006; Rizzo and Whitman 2020). Post-Keynesians focus on financialization, arguing that speculative activities undermine productive entrepreneurship and deepen inequalities (Foster 2010). Ecological economists call for “green entrepreneurship” to address inequality while prioritizing sustainability, critiquing traditional models that prioritize profit over environmental and social goals (Carroll and Khessina 2005).

Inequality and Entrepreneurship in the Austrian School

In the Austrian school, entrepreneurship is considered the cornerstone of economic processes (Kirzner 1997). Entrepreneurs identify opportunities, take risks, and meet consumer needs, driving innovation and resource allocation (Foss and Klein 2012; Baker and Nelson 2005). As a result, inequalities emerge naturally and are seen as a legitimate reflection of individual differences in talent, foresight, and effort (Rosen 1981).

For instance, Ludwig von Mises highlights the role of consumers in determining entrepreneurial success: “The real bosses, in the capitalist system of market economy, are the consumers. They, by their buying and by their abstention from buying, decide who should own the capital and run the plants. They determine what should be produced and in what quantity and quality. Their attitudes result either in profit or in loss for the enterpriser. They make poor men rich and rich men poor. They are no easy bosses” (Mises 2007, 20–21). Thus, entrepreneurial success and the resulting inequalities are not imposed but stem from voluntary market interactions. This perspective underscores that disparities are not inherently problematic but are a necessary part of a dynamic and efficient market system.

While the Austrian school accepts natural inequalities as a by-product of market efficiency, it draws a sharp distinction between these and artificial inequalities caused by state intervention (Hoppe 2013). Natural inequalities arise from free competition, where individuals succeed by innovating or meeting consumer demands. In contrast, artificial inequalities result from subsidies, protectionism, or regulations that unfairly favor specific actors (Rothbard 2006b; Holcombe 2018). Israel Kirzner underscores that entrepreneurship, as a discovery process, thrives on competition to eliminate inefficiencies (Kirzner 1973, 1997). However, state intervention disrupts this natural mechanism, creating artificial entrepreneurs whose success depends on political connections rather than on merit. This distinction is critical to understanding how state distortions exacerbate disparities beyond what markets would naturally produce (Ioannides 2000).

From the Austrian perspective, inequalities are not merely an outcome but also an essential signal within the market (Hayek 1976, 51). High profits signal unmet consumer demand and attract new entrepreneurs to profitable sectors. This dynamic fosters competition, spurs innovation, and, over time, tends to reduce disparities by improving goods and services for consumers. Friedrich Hayek (1976, 1–29) emphasizes that attempts to correct these inequalities through redistributive policies disrupt the market’s natural efficiency, ultimately harming both innovation and productivity. Consequently, inequalities in a free market are viewed not as obstacles but as mechanisms that guide resources toward their most effective uses (Yeager 1994).

The Austrian school offers a pointed critique of Thomas Piketty’s claim that the accumulation of capital and its returns, in which returns exceed economic growth (r > g), inevitably leads to rising inequality (Jones 2015). Austrians argue that in a free market, wealth is not static; it is constantly redistributed through entrepreneurial failures, market fluctuations, and innovation (Bylund 2016a). Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard maintain that wealth can only be sustained if it continues to meet consumer demands. Additionally, Austrians challenge the notion that state intervention can effectively address inequality, arguing that such measures often introduce new distortions, such as regulatory capture or cronyism, which exacerbate artificial disparities instead of resolving them (Block 2019; Munger and Villarreal-Diaz 2019).

Austrians place significant emphasis on the fluidity of economic positions in a free market. Unlike systems distorted by state intervention, free markets allow individuals to rise or fall based on their entrepreneurial abilities. Successful entrepreneurs may lose their fortunes if they fail to innovate, while new players can achieve success through creativity and effort. Rothbard critiques state-imposed barriers to entry, which hinder this natural economic mobility, asserting that the real distortions come from state intervention, which limits competition and creates artificial monopolies (Rothbard 2006). Social mobility, therefore, is seen as a defining feature of market-driven economies and a mechanism for mitigating inequalities over time.

To address the issue of artificial inequalities, the Austrian school makes several key policy recommendations (Godart-van der Kroon and Salerno 2022). First, they advocate for the elimination of state privileges, including subsidies and protectionist regulations, which distort competition (Bylund 2016b). Second, they emphasize the need to promote genuine competition, ensuring that entrepreneurial success is determined by innovation and consumer satisfaction rather than by political favoritism (Kirzner 1973). Third, Austrians call for a significant reduction in state intervention in order to allow markets to self-correct inefficiencies (Ikeda 2002; Mises 1998, 2011). Finally, they stress the importance of protecting private property, as secure property rights encourage investment, innovation, and wealth creation (Hoppe 2006). Together, these measures aim to foster a fairer economic environment where natural inequalities reflect genuine differences in contributions to society.

In summary, the Austrian school views entrepreneurship as the primary driver of natural inequalities, which arise organically from market processes (Foss and Klein 2012). These disparities are not only legitimate but also essential for economic dynamism, as they reward innovation and efficient resource use. However, Austrians strongly oppose artificial inequalities created by state interventions, which distort competition and reward political connections over merit (Rothbard 2000). By advocating for minimal government interference and fostering genuine competition, the Austrian perspective ensures that inequalities reflect the real value contributed by economic actors (Menger 2007; Priem 2007). This framework positions the free market as the optimal mechanism for promoting both innovation and fairness in society.

Acknowledging Piketty’s Case

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century presents a groundbreaking and meticulously researched analysis of the historical dynamics driving inequality in modern capitalism. By anchoring his argument in the long-term trends of the capital-income ratio and the tendency for the rate of return on capital to exceed the rate of economic growth (r > g), Piketty (2014) provides a compelling explanation for the widening gap between the wealthy and the rest. This rich-get-richer dynamic serves as a structural critique of modern economies, illustrating how wealth accumulation increasingly outpaces income from labor. His work raises the alarm about the potential return to levels of wealth concentration and inherited privilege that characterized nineteenth-century societies, threatening the democratic and meritocratic values of contemporary economies (Mijs and Savage 2020).

Piketty’s policy proposal of a progressive annual wealth tax, though theoretically aligned with his diagnosis of inequality, poses significant challenges in terms of implementation (Boushey, DeLong, and Steinbaum 2017). The envisioned global or regional wealth tax would require unprecedented levels of international cooperation, transparency, and enforcement to prevent capital flight and tax evasion (Zucman 2015). While Piketty argues that this tax would narrow the gap between the rate of return on capital and economic growth, reducing the accumulation of wealth at the top, critics contend that such measures could stifle innovation, savings, and productive investment. The technical and political feasibility of this solution, particularly in regions like the United States, remains highly questionable, given the prevailing resistance to even modest measures such as estate taxes or progressive income tax reforms.

Beyond its policy prescriptions, Piketty’s work challenges deeply held assumptions about the self-correcting nature of market economies. His analysis underscores the systemic forces that drive inequality, including the structural advantage of wealth owners, who can reinvest returns at higher rates, over those reliant on labor income. This critique raises uncomfortable questions about both the sustainability of capitalism if left unchecked and its capacity to deliver equitable outcomes (Schweickart 2010, 2009). However, addressing these structural imbalances requires a nuanced approach that goes beyond taxation. Investment in education, skills development, and broader access to economic opportunities could counterbalance the forces of inequality, ensuring that economic growth benefits a wider segment of society (Robinson 2012). Policies promoting corporate accountability and fair compensation structures, especially in the context of rising “supermanagers,” are equally critical (Dunne, Grady, and Weir 2018; Rosen 1981).

Ultimately, Piketty’s work is as much a call to reflection as it is a call to action. His meticulous empirical research and historical perspective provide invaluable tools for understanding inequality, while his proposed solutions invite further debate about how best to address the growing concentration of wealth. Whether or not one agrees with his conclusions, Capital in the Twenty-First Century forces policymakers, economists, and the public to confront the consequences of unchecked inequality. It challenges us to think critically about the intersection of economics, politics, and social justice in shaping a more equitable future. In doing so, Piketty has ensured that the debate on inequality will remain central to discussions about the future of capitalism and democracy for years to come.

Acknowledging the Problem: Growing Inequality

To dismiss Piketty entirely would be a mistake. Inequality in the West is rising, and libertarians often overlook this fact by focusing solely on the benefits of free-market outcomes (Otsuka 2005). Piketty identifies a significant issue: the growing concentration of wealth among the top 1 percent, which threatens to destabilize social and political structures. His observation that “every human society must justify its inequalities: reasons must be found because, without them, the whole political and social edifice is in danger of collapsing” underscores the importance of addressing this issue (Piketty 2020a, 1). While the free market can lead to natural disparities based on talent and effort, the wealth concentration we see today merits closer scrutiny, pointing to systemic issues beyond market forces.

Much of the inequality we witness today is not solely the product of free-market mechanisms but rather the result of state intervention that distorts competition. Government policies—such as subsidies, tax breaks for the wealthy, and regulatory favoritism—create artificial winners. This intervention allows certain actors to amass wealth through political connections, not innovation or productivity. As Murray Rothbard argues, “There is no distributional process apart from the production and exchange processes of the market; hence, the very concept of ‘distribution’ as something separate becomes meaningless” (Rothbard 2009, 1155). In a free market, wealth outcomes are tied to voluntary exchange, not to deliberate state-driven distribution. When the state interferes, it disrupts the natural market dynamics for entrepreneurs, exacerbating inequality in ways that free-market capitalism would not (Kirzner 1973).

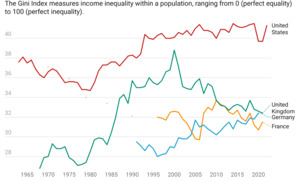

Top 1 Percent Net Personal Wealth Share over Time

Figure 1 displays the share of total wealth held by the top 1 percent in various countries, such as the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, from 1900 to the early twenty-first century.[2] A notable feature of the graph is the general downward trend in wealth concentration for all countries during the mid-twentieth century, particularly after the world wars, likely due to economic reforms, increased taxation, and social welfare policies aimed at wealth redistribution. For instance, the wealth share held by the top 1 percent in the United Kingdom saw a sharp decline from nearly 75 percent in the early twentieth century to below 25 percent by 1980. France, Germany, and the United States followed similar trajectories of declining wealth concentration, though some variations reflect differences in national policies.

From the 1980s onward, the graph shows a stabilization and even an upward trend in the United States and the United Kingdom, suggesting a reversal of earlier redistributive efforts. This period coincided with the rise of neoliberal economic policies, such as tax cuts for the wealthy and deregulation, which helped capital holders accumulate more wealth. The United States, in particular, shows a noticeable resurgence in wealth concentration among the top 1 percent, while France and Germany seem to maintain a more moderated wealth distribution. The share of global wealth held by the top 1 percent in developed economies, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, illustrates the broader trend of rising inequality since the 1980s. While this increase is particularly pronounced in the United States, it is less significant in Germany and more moderate or less visible in countries like the United Kingdom and France. Nevertheless, global inequality has significantly decreased since the first decade of the twenty-first century, even though the share of wealth among the top 1 percent in other parts of the world has remained relatively stable during this period.

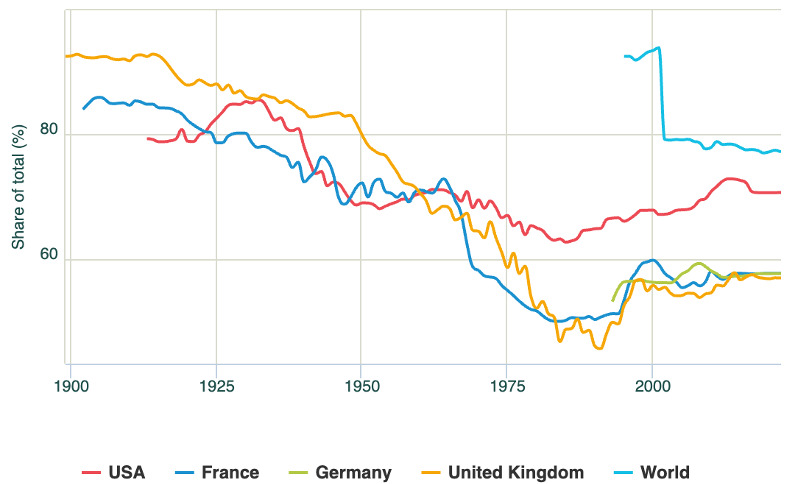

Top 10 Percent Net Personal Wealth Share over Time

Figure 2 highlights the increasing concentration of wealth among the top 10 percent of earners in countries like the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and globally over time. In the early twentieth century, the share of total wealth held by the top 10 percent was extremely high, exceeding 80 percent in most countries. Over the century, we observe a notable decline, particularly after the Second World War, which corresponded with a period of economic reforms, higher taxation, and social welfare programs aimed at redistributing wealth more equitably.

However, the trend shifts sharply around the 1980s. The wealth share of the top 10 percent begins to rise, especially in the United States and the United Kingdom, which reflects a broader global pattern of growing inequality in Western economies. This increase aligns with the rise of neoliberal economic policies—marked by tax cuts for the wealthy, deregulation, and privatization—which favored capital holders. In particular, the United States shows a sustained upward trend post-1980, with the wealth share of the top 10 percent nearing 70 percent by the early twenty-first century.

In contrast, France and Germany show a more modest increase in wealth concentration, attributable to their more robust welfare systems and a stronger regulatory framework, which counterbalanced the sharp rise seen in the Anglo-Saxon economies. Nonetheless, the data for these countries still suggests a gradual return to growing inequality, underscoring that even in social democracies, wealth concentration at the top is a persistent issue.

Overall, this graph emphasizes that while market forces play a role in wealth distribution, the sharp rise in wealth concentration at the top is primarily influenced by state policies that have disproportionately benefited the wealthy. This dynamic is crucial to understanding the systemic nature of inequality in the contemporary era, a central argument in Piketty’s work.

Bottom 50 Percent Net Personal Wealth Share over Time

Lastly, as shown in figure 3, the bottom 50 percent of earners show a stagnation or decline in wealth share over the past few decades. This reflects how state mechanisms disproportionately benefit the wealthy through crony capitalism and regulatory capture while leaving the working class with fewer opportunities to accumulate wealth.

Together, these graphs visually represent the increasing inequality within Western nations, underscoring that while some disparity is natural in a free market, much of today’s extreme inequality stems from the state’s interference in market dynamics. The role of cronyism, where the state picks winners through subsidies, regulations, and corporate favoritism, cannot be ignored.

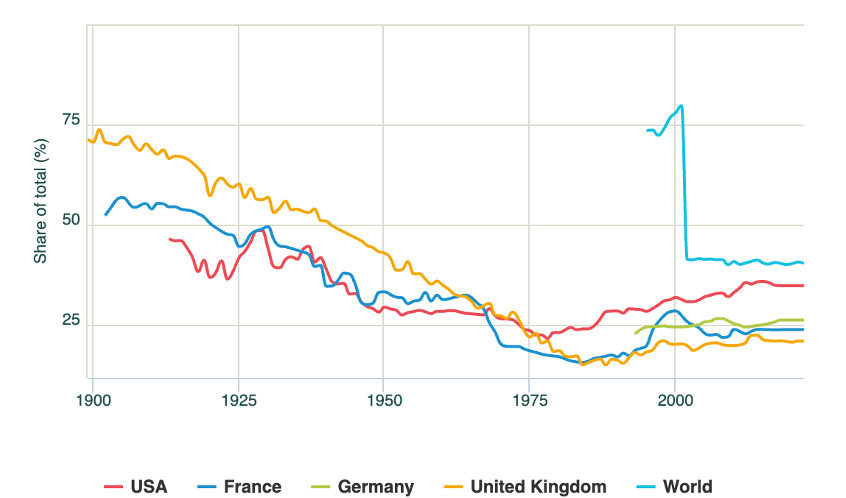

A Comparison of Income Inequality: A Gini Index Analysis of the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom

The Gini Index, which measures income inequality on a scale from 0 (perfect equality) to 100 (maximum inequality), reveals notable differences between Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Germany and France maintain relatively low levels of inequality, with Germany’s Gini value fluctuating between 28.0 and 32.4 and France’s between 31.5 and 37.1 over the observed years. While Germany’s income distribution has remained stable, France shows a gradual decrease in inequality, reflecting improved income distribution. In contrast, the United Kingdom experienced a sharp rise in inequality during the 1980s and early 1990s, reaching a peak of 38.8, likely due to structural economic changes and policy reforms. Although the United Kingdom’s inequality has declined slightly in recent years, it remains higher than in Germany and France.

The United States consistently shows the highest Gini value, highlighting significant and persistent income disparities. From a Gini value of 37.6 in the 1960s, it has climbed to over 41.0 in recent years, reflecting growing income concentration among wealthier segments of the population. This trend indicates systemic challenges in addressing income inequality, in stark contrast to the relative stability in Germany and the improvements seen in France. Overall, the data underscores the varying degrees of inequality among these nations, shaped by their economic structures and policy decisions.

The Role of the State: Unequal Access and Distortions

Piketty’s analysis notably fails to sufficiently account for how modern entrepreneurs and corporations amass wealth not solely through innovation or market forces but also through close ties to the state. This is the case also for many libertarian scholars, like Mises, who sometimes seem to glorify entrepreneurs without taking into account that the state can favor a certain type of entrepreneur (Hoppe 2013; Mises 1996). Many of today’s wealthiest entrepreneurs and business owners have built their fortunes by leveraging government policies through subsidies, bailouts, favorable regulations, and other forms of state intervention.[3] In Power and Market, Rothbard (2006b) provides one of the most precise and detailed microeconomics definitions of regulation within the Austrian school. He categorizes regulation as a form of “triangular intervention,” where a third party coerces two individuals into engaging in or refraining from a particular exchange. This intervention can affect the terms of exchange, the nature of the goods being exchanged, or the parties involved. Rothbard (2006b, chap. 3) identifies various forms of such intervention, including price controls, product controls (e.g., prohibitions, monopolistic privileges), mandatory cartels, licensing, safety standards, tariffs, immigration restrictions, labor laws, conscription, minimum wage laws, subsidies, market sanctions, and antitrust laws. Expansionary or restrictive macroeconomic policies can also affect the capacity of agents to finance themselves, save, or invest in the economy (Rothbard 2006). In these cases, the state effectively creates artificial entrepreneurs, whose success is based primarily on political connections and interventionism rather than on market innovation and differentiation.

Moreover, government intervention can influence the incomes and preferences of individuals, changing their consumption functions by applying fiscality, subsidies, and other types of regulation affecting their preferences.

The distinction between naturally and artificially successful entrepreneurs is crucial. Naturally successful entrepreneurs—those who achieve success through risk-taking, innovation, and serving consumer needs—create value in a free-market system and contribute to overall economic welfare. On the other hand, artificial entrepreneurs thrive in a system that rewards cronyism, regulatory capture, and rent-seeking behavior (Noll and Owen 1983). As Ludwig von Mises explains, “To assign to everybody his proper place in society is the task of the consumers. Their buying and abstention from buying is instrumental in determining each individual’s social position” (Mises 1996, 275). Under state-controlled systems, this dynamic is totally disrupted, and the state, rather than consumers, determines success, thus exacerbating inequality.

Moreover, Mises highlights that in a capitalist society, “the rich can more easily become poor, and the poor can more easily become rich” due to the fluidity of the market (Mises 1951, 438). In contrast, state intervention leads to a more rigid system where political favoritism overrides market forces. The role of distribution in this context also becomes essential. As Rothbard explains, “There is no distributional process apart from the production and exchange processes of the market; hence the very concept of ‘distribution’ becomes meaningless on the free market” (Rothbard 2011, 321). The state’s interference in distribution not only distorts production but also artificially limits the social mobility that would otherwise exist in a free market.

To understand how state interventions create distortions and favor artificial entrepreneurs, let us examine examples from three main markets: the goods and services market, the capital and money market, and the labor market.

The Goods and Services Market

State intervention in the goods and services market often takes the form of fiscal policies, subsidies, and regulations that alter competition and consumer preferences. Examples follow:

-

Automobile industry. High taxation on fossil fuel vehicles combined with subsidies for electric cars can reshape entire sectors. Such policies may stifle competition, artificially favoring certain technologies while disadvantaging others, regardless of their market efficiency or consumer demand (Levinsohn 1988; Ma, Du, and Wu 2019).

-

Cultural industries. In less obvious sectors, such as the music industry, public policies play a subtle yet significant role. For example, mandatory school programs may prioritize modern music genres like rap over traditional classical music, thereby influencing cultural production and consumption patterns (Peacock 1994).

-

Retail and e-commerce during COVID-19. During the pandemic, lockdown measures forced individuals to rely heavily on online shopping platforms (Lopes and Reis 2021; Roggeveen and Sethuraman 2020; Sayyida et al. 2021). This situation disproportionately benefited large e-commerce players, such as Amazon, while harming local businesses (Albanesi and Kim 2021, 19). By limiting market access, these policies exacerbated the dominance of oligopolistic distributors in the retail sector.

The Capital and Money Market

The capital and money market is particularly susceptible to distortions through monetary and fiscal policies. Here are examples:

-

Monetary policy. Expansionary monetary policies, such as prolonged periods of low interest rates set by central banks, disproportionately benefit financial markets (Mises 2009; Rothbard 1994). These policies enable companies in the finance and technology sectors to access cheap capital, often at the expense of the agricultural or industrial sectors, which may struggle to compete, as happened during the COVID-19 crisis (Christl et al. 2024).

-

Public investment in start-ups. In France, the Banque publique d’investissement (BPI) illustrates how public funding can influence market dynamics (Klein et al. 2010). By allocating venture capital financed through taxation, the BPI often favors start-ups based on criteria such as environmental, social, and governance compliance rather than purely on profitability or market potential (Aydoğmuş, Gülay, and Ergun 2022; Daugaard and Ding 2022; Chan-Tung 2013). This approach distorts competition and channels resources into specific industries regardless of market demand.

The Labor Market

The labor market is another domain where state intervention alters natural dynamics. Examples include the following:

-

Fiscal policies and managerial salaries. Expansionary fiscal policies, such as government-subsidized wage programs, can inflate managerial salaries in specific industries or public sector roles, regardless of productivity or market forces (Schuettinger and Butler 1979). This creates artificial incentives and disrupts the allocation of talent across sectors.

-

Minimum wage laws and labor regulations. Strict labor regulations, such as minimum wage laws or mandated benefits, may disadvantage small businesses while favoring larger corporations that can absorb these costs (Ashenfelter and Smith 1979; Welch 1974). This can lead to a concentration of power and reduced competition in labor-intensive sectors.

These examples demonstrate how state interventions create imbalances, favoring politically connected actors or sectors over others. Such distortions undermine market efficiency, discourage innovation, and exacerbate inequality by enabling artificial entrepreneurs to thrive at the expense of natural, market-driven competition.

Naturally versus Artificially Successful Entrepreneurs

In a genuinely free market, success naturally comes to those who take risks, innovate, and efficiently allocate resources. These natural entrepreneurs operate in a competitive environment and drive economic growth and wealth creation. They meet consumer demand through value-added innovation, offering new products and services, thereby contributing to societal welfare. Their success is tied to their ability to respond to market signals, adjust to competition, and thrive through voluntary exchanges. As Ludwig von Mises explained, “The only source from which an entrepreneur’s profits stem is his ability to anticipate better than other people the future demand of the consumers” (Mises 1996, 288). This ability to foresee and meet consumer needs is the hallmark of a natural entrepreneur’s success in a free market.

We have numerous examples of such natural entrepreneurs who exemplify these principles. For instance, Elon Musk has achieved remarkable success through his innovative ventures like Tesla and SpaceX, responding to market demand for sustainable and advanced technologies by taking significant risks and efficiently allocating resources (Bosanquet 2023; Muegge and Reid 2019). Similarly, Steve Jobs revolutionized consumer electronics at Apple by anticipating consumer needs and delivering groundbreaking products like the iPhone. Jeff Bezos built Amazon into a global giant by efficiently meeting consumer demand for convenience and variety, leveraging technology to streamline operations and scale the business organically (Gugler, Szücs, and Wohak 2023). Sara Blakely, founder of Spanx, demonstrated entrepreneurial ingenuity by identifying a gap in the shapewear market and growing her brand through creative marketing and innovation, all without state subsidies. Lastly, Richard Branson’s Virgin Group showcased the natural entrepreneur’s spirit as he successfully navigated various industries, from music to aviation, through taking calculated risks amid open-market competition. These examples highlight how natural entrepreneurs contribute to economic progress by responding to consumer demand and driving innovation without reliance on state interventions.

However, when the state steps in to protect certain businesses or industries through subsidies, tariffs, excessive regulation, or other forms of intervention, the market is no longer a level playing field. This creates artificial entrepreneurs—businesses or individuals whose success is based not on market forces but on political connections and state support. These entrepreneurs thrive not by providing better products or services but by capitalizing on state-created advantages, such as monopoly rights, regulatory capture, or barriers to entry that stifle competition (Ikeda 2002; Mises 2011, 1998). Mises emphasizes that the role of the entrepreneur is to navigate future uncertainties and select projects that meet the public’s most urgent needs (Bylund and McCaffrey 2017; Knight 1921). Yet state intervention distorts this natural process (Mises 1974, 117).

Examples of artificial entrepreneurs and enterprises highlight the detrimental effects of state distortions (Munger and Villarreal-Diaz 2019). Individuals such as Bernard Tapie, Patrick Drahi, and Xavier Niel in France have been criticized for leveraging political connections and state interventions to build their business empires, often bypassing the competitive pressures of free markets (Winter 2007). For instance, Xavier Niel benefited significantly from the deregulation of the French telecom industry under President Nicolas Sarkozy, which gave Niel the privilege of competing in a market previously dominated by SFR, Orange, and Bouygues (Berne, Vialle, and Whalley 2019). Similarly, Carlos Slim’s dominance in the Mexican telecommunications sector was facilitated by government-granted monopoly rights, which allowed Slim to suppress competition and maintain market control (Winter 2007).

Corporate examples further illustrate this phenomenon. Solyndra, a US solar energy company that received over $500 million in government loans, epitomizes the pitfalls of state support overriding market viability, in this case ultimately leading to inefficiency and failure (Caprotti 2017; Flood 2013; Olson and Biong 2015). Boeing, while a renowned innovator, relies heavily on defense contracts, which confer an artificial competitive advantage (Pritchard and MacPherson 2004). Likewise, US government–sponsored enterprises such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac gained dominance in the mortgage sector through implicit state backing, contributing to financial distortions and crises (Frame et al. 2015). In the pharmaceutical industry, many companies exploit state-enforced intellectual property rights to extend monopolies, leading to artificially high drug prices and restricted competition (Kourouklis 2021; Xu, Wang, and Liu 2021; Yang and Xu 2023).

These cases demonstrate how artificial entrepreneurs and enterprises thrive not through innovation or market-driven success but through state-created advantages. This reliance on political favors and intervention distorts economic efficiency, hinders fair competition, and perpetuates inequality, undermining the principles of a free-market economy.

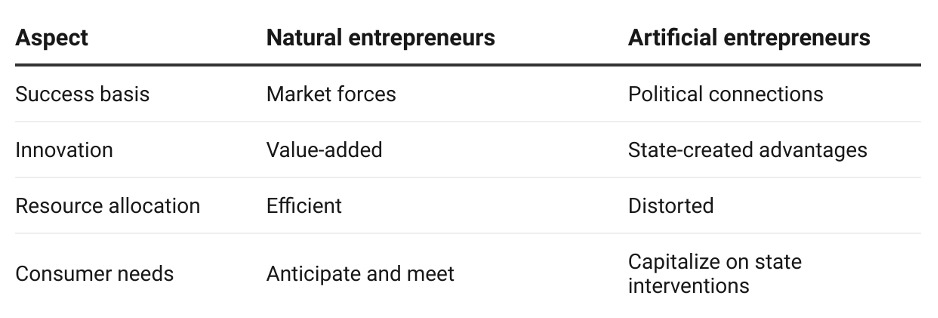

Table 1 highlights the fundamental differences between naturally and artificially successful entrepreneurs. It contrasts their success drivers, innovation approaches, resource allocation, and responsiveness to consumer needs within the frameworks of free-market dynamics and state intervention. The visualization underscores the role of market forces versus that of political connections in shaping entrepreneurial outcomes.

It is important to acknowledge that the distinction between natural and artificial entrepreneurs, while useful for analytical purposes, can sometimes blur in practice. Certain entrepreneurs, such as Elon Musk, initially embody the archetype of a natural entrepreneur: his success with ventures like PayPal, Tesla, and SpaceX was built on innovation, risk-taking, and market responsiveness. However, his status becomes more ambiguous when one considers his later reliance on government contracts and subsidies. For instance, SpaceX benefited significantly from NASA contracts and government support, leading to criticisms of a quasi monopoly in the private space industry. Similarly, Jeff Bezos, another emblematic natural entrepreneur through the success of Amazon, has faced scrutiny for his engagement in lobbying efforts and disputes over government contracts, such as those involving the US Department of Defense and cloud computing. These examples highlight that the boundaries between natural and artificial entrepreneurship are not always clear-cut. Entrepreneurs who emerge from competitive markets can, over time, leverage state support or regulatory advantages to solidify their dominance, making their classification less straightforward. As such, while the distinction remains valuable for understanding broader economic trends, it must be applied with the awareness that real-world cases often involve complexities and overlapping dynamics.

Piketty’s observation of growing inequality is, in many cases, a reflection of this state-created dynamic. Large corporations and wealthy individuals can leverage their influence over government policy, securing benefits that protect their wealth and stifle competition. This is the result not of free-market capitalism but of cronyism and state intervention. Naturally successful entrepreneurs achieve their success independently, through their ability to anticipate market demand and efficiently meet consumer needs. In contrast, artificially successful entrepreneurs exploit state interventions to gain unfair advantages, benefiting from governments’ subsidies, enforcement of intellectual property rights, or expansionary monetary policies.

The distinction between natural and artificial success is crucial because while natural entrepreneurs contribute to overall economic welfare, artificial entrepreneurs thrive in systems that distort market forces, leading to the misallocation of resources.[4] As Mises notes, “An entrepreneur cannot be trained”—true success comes from seizing opportunities and displaying judgment, foresight, and energy, not from benefiting from state-sponsored privileges (Mises 1996, 311). By artificially elevating certain actors, state intervention exacerbates the very inequality that Piketty critiques, resulting in a system where wealth is concentrated not because of market innovation but because of political favoritism.

Piketty’s Flawed Solutions: Taxation as a Cure?

In Capital and Ideology, Thomas Piketty (2020a) expands on the themes introduced in Capitalism the Twenty-First Century (Piketty 2014), focusing on inequality’s historical and global nature and how political and ideological systems sustain it. Piketty argues that inequalities are not natural or inevitable but result from deliberate political and economic choices. He emphasizes that ideologies justifying inequality—such as those glorifying “job creators” in the United States or “premiers de cordée” in France—are fundamental to maintaining these disparities. Piketty believes these systems are unsustainable and will ultimately be replaced, much like past ideologies. However, his proposed solution of progressive taxation, including a wealth tax of up to 90 percent for the wealthiest individuals, and the creation of an international registry of assets raises significant concerns about its effectiveness and unintended consequences.

Piketty’s proposal of progressive taxation mirrors historical policies in the United States and other countries where high tax rates on income and inheritance were implemented, particularly between 1950 and 1980. He argues that such policies coincided with strong economic growth. Yet, as Ludwig von Mises points out, “Taxing profits is tantamount to taxing success” (Mises 1974, 121). Heavy taxation, especially on capital, stifles innovation, discourages risk-taking, and punishes those who succeed through entrepreneurship. In Piketty’s framework, wealth redistribution is prioritized, but the result is often the expropriation of the most productive members of society. Mises further argues that “progressive taxation of income and profits means that precisely those parts of the income which people would have saved and invested are taxed away” (Mises 2006, 84). This diminishes capital investment, which is crucial for long-term economic growth and productivity.

Furthermore, Piketty’s notion of social and temporary property disregards the importance of private property as a cornerstone of economic freedom. Mises (1996, 734) discusses the transformation of taxation into “weapons of destruction” as particularly relevant here. Rather than fostering economic equality, excessive taxation leads to state control over resources and stifles entrepreneurial activity. Estate taxes, for instance, as Mises points out, “are no longer to be qualified as taxes. They are measures of expropriation” (Mises 1974, 32). This highlights the dangers of wealth taxes, as proposed by Piketty, where the aim shifts from equitable taxation to outright expropriation of successful entrepreneurs, leading to decreased innovation and economic stagnation.

The problem with Piketty’s argument is that it does not examine the difference between naturally and artificially successful entrepreneurs using a holistic method. His methodology tends to homogenize groups with various profiles.

Public and Private Orders: Final Reflections and Policy Implications

A key conclusion of this article is the need to reframe how economic agents and policymakers perceive entrepreneurship, inequality, and public policy. A critical question must be posed: to what extent does an entrepreneur’s success stem from the spontaneous order of the free market versus from state-driven interventionism? Answering this question would have far-reaching implications across economic, political, and social dimensions.

From an economic perspective, such an inquiry would challenge conventional assumptions about value creation, the distribution of wealth, and the role of innovation in driving economic progress (Noll and Owen 1983; Holcombe 2018). Policymakers and citizens alike would be better equipped to distinguish between wealth derived from genuine entrepreneurial risk-taking and innovation and that accumulated through political favoritism and regulatory capture (Noll and Owen 1983; Holcombe 2018). This distinction is essential for crafting policies that foster fair competition and discourage crony capitalism.

Politically, greater awareness of the state’s role in granting privileges and distorting markets could prompt a reevaluation of power structures. It would expose how state-sanctioned advantages—subsidies, monopolies, and favorable regulations—consolidate wealth among artificial entrepreneurs, often at the expense of market efficiency and social mobility (Bylund 2016a; Decker 2023). Recognizing these dynamics could lead to increased respect and appreciation for naturally successful entrepreneurs, who embody the principles of merit and innovation in a competitive marketplace.

Socially, this reevaluation would have the potential to alter perceptions of wealth and hierarchy. By highlighting the contributions of natural entrepreneurs and exposing the dependence of artificial entrepreneurs on state support, societies could move toward accepting a more organic and merit-based hierarchy. Such a shift would help frame capitalism as a fair system where success is determined by market signals and consumer choice rather than by political privilege (G. H. Smith 1979).

As Hans-Hermann Hoppe (2013, 5) observes in Natural Elites, Intellectuals, and the State:

Rich men exist today, but more frequently than not they owe their fortunes directly or indirectly to the state. Hence, they are often more dependent on the state’s continued favors than many people of far-lesser wealth. They are typically no longer the heads of long-established leading families, but “nouveaux riches.” Their conduct is not characterized by virtue, wisdom, dignity, or taste, but is a reflection of the same proletarian mass-culture of present-orientation, opportunism, and hedonism that the rich and famous now share with everyone else. Consequently—and thank goodness—their opinions carry no more weight in public opinion than most other people’s.

Hoppe’s critique underscores the societal consequences of conflating state-supported wealth with genuine market success. By disentangling these two forms of entrepreneurship, we can better appreciate the contributions of natural entrepreneurs while diminishing undue reverence for wealth built on state intervention. Ultimately, this reflection invites a broader cultural and intellectual shift toward recognizing the virtues of free-market capitalism and its capacity to foster both fairness and innovation.

Extending the Logic into Policy Recommendations and Practical Applications

This article calls for a reevaluation of our understanding of inequality through distinguishing between natural and artificial entrepreneurship. The implications of this distinction are profound: if most successful entrepreneurs derive their wealth from political favoritism and state interventions, then inequality reflects systemic distortions rather than free-market dynamics. Conversely, if success primarily stems from natural entrepreneurship, it underscores the fairness of markets in rewarding innovation and risk-taking. Recognizing this divide can reshape moral, economic, and political analyses of inequality, emphasizing the need for policies that prioritize merit over favoritism.

To foster a society dominated by natural entrepreneurs, policy must pivot toward strengthening private property rights and free-market competition. This includes reducing subsidies, dismantling protectionist regulations, and simplifying bureaucratic barriers that favor entrenched actors. Tax reforms should avoid punitive wealth redistribution and instead promote innovation and productive risk-taking. Moreover, increased transparency and accountability in public spending are essential to curtailing cronyism and ensuring fair competition (Block 2019). With inflated public spending and overregulation, particularly in the European Union, we remain far from achieving a market environment free of state distortions. Redirecting policy focus in these ways will help create a dynamic and equitable economic order driven by genuine entrepreneurial talent.

Long-Term Consequences of Inaction

Failing to distinguish between natural and artificial entrepreneurship poses significant risks to social, economic, and political stability. If growing inequalities are primarily the result of state-driven distortions—such as subsidies, protectionism, and regulatory capture—this incentivizes aspiring entrepreneurs to engage in crony capitalism rather than in innovation. Such a trend could exacerbate wealth concentration, reduce competition, and further entrench systems of privilege, fueling discontent and undermining trust in both markets and government institutions (Bylund and McCaffrey 2017). This issue is especially pressing in light of rising public spending and regulatory inflation across many Western economies, where interventionism is creating increasingly uneven playing fields.

Libertarians must take a leading role in addressing this challenge, particularly in a world often hostile to free-market ideas. By analyzing and explaining the differences between natural and artificial entrepreneurship, scholars and researchers can help counter anticapitalist narratives and foster a more nuanced understanding of entrepreneurial success (Klein and Bylund 2014). Raising public awareness through rigorous qualitative and quantitative research is crucial for demonstrating how free markets can promote fairness and opportunity. Without such efforts, unchecked artificial entrepreneurship may lead to an increasingly oligarchic society where political connections, rather than merit and innovation, determine success. This undermines the principles of competition and meritocracy that are foundational to a thriving and equitable economic system.

New Research Directions and Empirical Tests

To deepen our understanding of the distinction between natural and artificial entrepreneurship, further research is essential. For example, analyses of the world’s top fortunes could incorporate a range of sources, such as biographies, financial statements, legislative records, and policy shifts over time. These studies would benefit from an interdisciplinary approach, drawing insights from economics, law, political science, and sociology to uncover how state interventions shape entrepreneurial success.

Future research could empirically test the impact of state intervention by comparing sectors with heavy government involvement—such as defense, finance, and healthcare—to less regulated industries. This comparative analysis would illuminate the extent to which political connections influence wealth accumulation and market outcomes. Additionally, interdisciplinary studies could explore how state policies such as subsidies or licensing requirements affect social mobility and the distribution of opportunities. By combining political economy with sociology, researchers could provide a more holistic view of how interventionism reinforces or disrupts economic hierarchies. Such efforts would build a robust empirical foundation for advocating policies that promote genuine free-market competition.

Conclusion

In addressing the pressing issue of rising inequality, it is essential to go beyond Thomas Piketty’s analysis and explore the proper drivers of wealth concentration. While Piketty rightly identifies the growing disparity between the rich and the rest of society, his proposed solutions of heavy taxation and increased state control fail to address the root cause of the problem: state intervention itself. As this article has shown, much of the inequality we see today is not a natural consequence of free-market capitalism but rather the result of cronyism, regulatory capture, and other forms of state-sponsored favoritism that create artificial entrepreneurs.

By distinguishing between natural entrepreneurs—those who succeed through innovation and market competition—and artificial entrepreneurs, whose success is built on political connections and state privileges, we better understand how state intervention distorts markets and exacerbates inequality. Piketty’s calls for higher taxation would not remedy this problem but further entrench it by empowering the state mechanisms contributing to the rise of artificial wealth.

The libertarian solution lies in reducing state interference in the economy, dismantling crony capitalist structures, and promoting a free market where success is determined by consumer choice and innovation, not government favoritism. Rather than resorting to wealth redistribution through taxation, we should focus on creating an environment where all entrepreneurs have equal opportunities to thrive. Limiting the state’s power can foster a more equitable society where wealth is earned, not politically granted.

In an interview discussing Capital and Ideology, Piketty (2020b) emphasizes that every society must justify its inequalities or risk collapse. He argues that inequality results from political and ideological choices rather than from natural forces. To democratize economic power and reduce wealth concentration, Piketty (2020a) proposes significant reforms, such as progressive taxation of up to 90 percent for the wealthiest, an international registry of assets, and universal capital endowments for citizens. He also advocates for environmental measures, including a carbon card system and progressive carbon taxes, to address emissions equitably.

All data used in this article was collected in September and October 2024. The way the World Inequality Database interprets its data appears to have changed since, so recreating my graphs on the World Inequality Database website will yield different graphs.

Unfortunately, I could not find solid qualitative and quantitative research on this subject with strong case studies (Dingwerth and Eckl 2022; Flanigan and Freiman 2022; Prinz 2016).

More research on this topic is needed.