Friedrich Hayek was arguably the most influential thinker to emerge in the Austrian school of economics in the twentieth century. He has rightfully been considered a pioneer and early adopter of complexity theory, emphasizing the importance of emergent properties in social systems (Lewis 2012; Lovasz 2023), but his evolutionary thinking is still not well understood in relation to recent scientific advances in the field. Although the Austrian school has always emphasized the dynamic nature of economic decisions and institutions, it was Hayek who developed the role of evolutionary thinking in economics in a deeper and more consistent and comprehensive way (see Kwasnicki 2018 for a comparison with competing schools).

Hayek’s evolutionary thinking took its final shape and achieved central importance in his theory late in his life, possibly under the influence of his friend Karl Popper. While it is possible to find the seeds in earlier books like The Constitution of Liberty or in Hayek (1967), the topic was only firmly stated in the epilogue of Law, Legislation and Liberty (2013) and developed further in The Fatal Conceit (1988), his last major work. Although maybe too abstract and lacking empirical support at the time, Hayek’s contributions were bold and original, defying well-established dogmas like methodological individualism in economics and its counterpart, individual selection in sociobiology, assuming individual motivations based on relative position rather than absolute gains, establishing a clear-cut separation between rules governing face-to-face interactions and exchange with strangers, and claiming that rationality and the mind are products rather than causes of the cultural evolution process that gave rise to the extended order, among others. Nevertheless, in spite of their interest, no significant development followed Hayek’s pathbreaking work in the subject after his death. In the last two decades, however, scientific advances in the fields of behavioral economics, psychology, evolutionary anthropology, and biology have put into question basic assumptions and conclusions of both neoclassical economics and evolutionary psychology and seem to confirm to a surprising degree Hayek’s conjectures.

My aim in this article is twofold. First, I will show how the new scientific findings support Hayek’s perspectives but not the more traditional libertarian position, thereby vindicating Hayek’s evolutionary contributions. Second, I will argue that the new theories that propose group selection as a major drive in human evolution, including Hayek’s own version, are also being used to support what could potentially be considered a totalitarian collectivist ethics and social engineering that probably few libertarians would agree with. I will argue that Hayek’s own view is more in line with the correct interpretation of cultural group selection.

The essay is structured in five sections: I start with a brief summary of Hayek’s model and its relations to the mainstream alternatives. I then describe three different theories recently proposed by different scholars that seem to support Hayek’s perspective.

Hayek’s Model of Societal Evolution

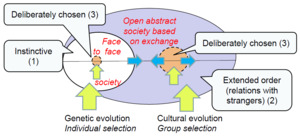

Hayek apparently took his evolutionary ideas from two sources (Caldwell 2000; Marciano 2009; Ebenstein 2003; Meyer 2006; Angner 2002; Witt 1994): first, from the long tradition of the Austrian school of economics, through Carl Menger, which was heavily influenced by the Scottish enlightenment philosophers and economists (e.g., Hume, Hutcheson, and Smith), and second, from Charles Darwin himself and his twentieth-century followers, such as Carr-Saunders, at the London School of Economics and Oxford University. Hayek was well aware of the recent developments in the new field of sociobiology that succeeded in applying the gene-centered view of Darwinian evolution to human social behavior, citing E. O. Wilson’s classic Sociobiology: The New Synthesis and important articles like those of biologist Robert Trivers in Hayek (2013). He actually criticized the field for assuming that all human values are either the product of genetic evolution (instincts) or the product of rational thought. Although this can be considered a gross simplification, the gene-centered view that had become mainstream in evolutionary biology at that time, and that was admirably explained by Dawkins (1976), discarded the possibility of any human traits having evolved from selection at the group level (for the benefit of the group) so that genes only favor individual traits for helping kin (kin selection) or reciprocal altruism (mutually beneficial repeated interaction with the same partners). Any other form of cooperation must be nongenetic and exclusive of humans, who can consciously detect fitness gains and engage in mutualistic agreements with strangers. Hayek, on the contrary, distinguished between three types of evolved rules of conduct (depicted in figure 1 below): those evolved through genetic evolution (type 1) that can only apply to face-to-face interaction situations (at the level of the family or small group), those evolved through cultural group selection for dealing with a large number of strangers in the “open abstract society” (type 2), and those that come from the rational choice of individuals (type 3) and that have been shaped by the rules of conduct in type 2 (its explicit evolution was never clearly explained).

Mind and culture developed concurrently and not successively. . . .

Man did not adopt new rules of conduct because he was intelligent. He became intelligent by submitting to new rules of conduct. . . .

The conduct required for the preservation of a small band of hunters and gatherers, and that presupposed by an open society based on exchange, are very different. But while mankind had hundreds of thousands of years to acquire and genetically to embody the responses needed for the former, it was necessary for the rise of the latter that he not only learned to acquire new rules, but that some of the new rules served precisely to repress the instinctive reactions no longer appropriate to the Great Society. (Hayek 2013, 495–96)

Although group selection was proposed by Darwin himself to account for the paradox of extensive human altruism, it went out of fashion after a famous debate in biology in the 1970s. Few people at the time defended its logical possibility, but Hayek boldly assumed that type 2 rules of conduct, appropriate for interaction with unknown others in large groups, were culturally group selected: those groups with more beneficial rules thrived and left more offspring, outcompeting those with less successful rules. Group selection could work through conflict (wars) or imitation, but imitators were not considered rational: they were often not conscious of the value embodied in the rules they were blindly imitating: “We must completely discard the conception that man was able to develop culture because he was endowed with reason. What apparently distinguished him was the capacity to imitate and to pass on what he had learned. . . . Man has certainly more often learnt to do the right thing without comprehending why it was the right thing, and he still is often served better by custom than by understanding” (Hayek 2013, 489–90).

But how and why were some individuals being imitated by others in the same group? Hayek assumes that impersonal type 2 interactions require each individual to maintain a sphere of freedom to choose behavior (represented by the dotted circles inside figure 1), and those behaviors that are considered better for whatever reason are imitated and gradually become fixed in the population within the type 2 set. Hayek also considers the main motivation for individual choice to be gaining the esteem of others in the group, which improves one’s relative position rather than resulting in an absolute welfare gain—“guided less by the desire to be able to consume much than the wish to be regarded as successful by his fellows who pursued similar aims” (Hayek 2013, 497). But for Hayek the success of the selection process is always measured in terms of group reproduction. “Most of these steps in the evolution of culture were made possible by some individuals breaking some traditional rules and practicing new forms of conduct—not because they understood them to be better, but because the groups which acted on them prospered more than others and grew” (493).

Curiously, Hayek apparently did not realize that a proper cultural traits selection process could be driven by the rate of reproduction of the traits themselves rather than by the individuals who hold the traits in their brains (what was later called “memetic theory” was first proposed by French sociologist Gabriel Tarde as early as 1903 and much later by Dawkins in 1976).[2]

The horizontal arrows depicted in figure 1 represent another important feature of the dynamic system envisioned by Hayek: there is a tendency or pressure for rules of conduct in type 1—appropriate for face-to-face interactions—to invade the domain of type 2 rules (through atavistic moralists who do not distinguish between both domains and want to apply egalitarian or paternalistic rules to the extended order) and for rational rules of conduct of type 3 to do the same (social reformers from Plato, through the Enlightenment, to the social engineers of the utopian and Marxist traditions). “In a culture formed by group selection, the imposition of egalitarianism must stop further evolution” (Hayek 2013, 503). Egalitarianism is destructive not only because it distorts the system of signals used in the extended order (type 2 rules of conduct) that adjusts the mutually beneficial behavior of individuals who do not know or understand the needs of others they indirectly serve “but even more through eliminating the one inducement by which free men can be made to observe any moral rules: the differentiating esteem by their fellows” (Hayek 2013, 502).

Hayek’s view not only rejects utilitarian conceptions of the economy but also the universal assumption of methodological individualism: the emergent properties of a complex system that has evolved through a cultural group selection process cannot be derived from the characteristics of individual minds and motives. This conclusion was also shared at the time by Hayek’s friend and colleague Karl Polanyi (1977), who also defended the view that structures of knowledge are implicit and can never be made entirely conscious or explicit. This justifies Hayek’s insistence on the impossibility of predicting and understanding the outcomes of the extended order by rational means, but it does so at the cost of endowing the products of this kind of selection (inherited traditions) with a logical legitimacy that, taken to the normative realm, could potentially serve to rationally justify conservatism, not unlike how Darwinism was used in the past to morally justify eugenics and other social excesses.

I will now explain three different approaches based on relevant scientific findings that challenge part of the theoretical apparatus backing libertarianism and neoclassical economics but that simultaneously confirm to an important extent Hayek’s evolutionary thinking.

The Darwinian Economy

The existence of individual actions that generate some kind of external effects has always been recognized in economics and has also limited definitions of individual rights based on “no harm” properties since John Stuart Mill’s definition in On Liberty. In the 1960s, the American economist Ronald Coase offered a decentralized solution workable when transaction costs are low, but recent evidence suggests that externalities in consumption might be everywhere. Layard’s (2006) happiness studies on the Easterlin paradox show that individual reported happiness is not related to wealth but to income inequality—wealth might be a relative concept or a positional good, an idea that recalls Thornstein Veblen’s old theory of conspicuous consumption. Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) also provide extensive evidence for the inverse relation of income inequality to a wide range of social problems, from health to crime rates. Assuming that a large number of consumption goods are only valued in relation to others’ consumption levels has led some economists like Robert Frank (2011) to propose a paradigm change from the neoclassical economic theory based on absolute values to a “Darwinian” economics in which individual preferences and value depend essentially on context and relative position. Since the fundamental theorems of welfare economics depend on the first framework, a major revision of the theory is needed in which fiscal policies like taxing consumption would be unambiguously better for all and might be rationally accepted by even the strictest libertarian.

How do these new facts affect Hayek’s libertarianism in its final evolutionary form? In my opinion, since Hayek presupposes individuals motivated precisely by their position in the social ranking, agreeing on Frank’s conclusions should not be a problem for them. The new evidence not only does not seem to alter significantly Hayek’s system but should actually reinforce the likelihood of his initial assumptions, compared to what most neoclassical economists would be willing to accept. In fact, Hayek’s evolutionary approach adds a realistic layer to the “Darwinian economy” proposed by Frank in two points: (1) Frank simply assumed that individual preferences based on relative position and relative income are the preferences that evolution by natural selection would predict; and (2) psychological preferences based on relative position are morally relevant, and maximizing a welfare defined by them should be a government’s or community’s main ethical goal.

By contrast, Hayek considered that the individual’s concern with being esteemed by others (which, for Frank, leads to a costly and inefficient status race) and the social norms or institutions that respect a certain individual sphere of freedom of action are social rules of conduct that themselves emerged as outcomes of the evolutionary process of cultural group selection. Both positional preferences and individual rights, therefore, work together to guarantee the appropriate incentives and the appropriate field of competition for the generation of new variations of behavioral rules that are susceptible to being imitated by others. Without them, the cultural group selection process would generate less innovation and ultimately less beneficial and adaptive rules in the group competition process. In fact, Hayek’s approach not only seems more complete and consistent but, even if it were judged in strictly utilitarian terms, the inefficiency and waste of positional competition and status seeking could be considered a moderate social cost to pay in exchange for the cultural innovation produced. Free markets that align individual prestige and success with serving the interests of others will assure that average and total wealth increase even when individuals are concerned with relative wealth only. Moreover, corrections of the system through taxes that do not take this effect into account could in fact be very damaging for society (both in terms of long-run welfare achieved and reduced degree of adaptation). Leveling income through an egalitarian ethos could be disastrous.

The Moral Economy

A second set of empirical results, this time from the behavioral economics literature, shows that monetary incentives to increase the supply of some activities sometimes backfire by crowding out intrinsic prosocial motivation in contexts where this second component of motivation is likely to be present. Offering moderate amounts of money to blood donors, for example, tends to decrease the supply of blood in the market. The most likely explanation of these phenomena is that, again, context matters. Humans like to follow existing social norms, but when social norms prescribe a given prosocial behavior, changing the decision context with monetary incentives makes it socially acceptable to be greedy, in which case a different set of preferences takes the lead in the decision. Different experiments with economic games like the public-good game, the dictator game, and the gift-exchange game—like those in Fehr and Gächter (2002)—prove that, contrary to game-theoretic predictions backed by the rational actor model, humans are altruistic toward strangers even if they cannot expect any reciprocal compensation. There are still some cultural and individual differences, but the result has proven so robust (see Henrich et al. 2001 for an extensive study on the subject) as to put into question entirely the Homo economicus model’s assumption that self-interest is the most important motivation of economic agents.

The overwhelming evidence for true (nonmutualistic) altruism in humans has not only shaken the foundation of economic theory but has also obliged evolutionary scientists to revise the existing theories on the evolution of altruism. We said before that purely altruistic actions toward strangers should be eliminated by natural selection, as Darwin himself clearly saw. Since group selection had already been considered unlikely for humans, the only possibility left is to consider altruism a side-effect of a sudden environmental change by which we mistakenly treat strangers as if they were kin or friends because our instincts are adapted to living in small groups. The problem with this view is that the most recent estimates (see, for example, Bowles and Gintis 2011 for a comprehensive survey) show that our hunter-gatherer ancestors in the Pleistocene lived in large groups of about 150 individuals. This puzzle has led to the development of new evolutionary models to explain altruism when dealing with Hayek’s “open abstract society,” which we shall comment on in the next section. But for now it is enough to acknowledge that the nature of the open abstract society is much more similar to that of the face-to-face society (in figure 1) than previously thought. This recently led Samuel Bowles to advocate public policies that take into account the trade-off between pure exchange or monetary incentives and existing prosocial intrinsic motivation (Bowles 2016). The horizontal arrow in figure 1 that makes the type 1 rules of conduct invade the type 2 might have a rationale when there is a considerable overlap between both sets (possibly at the level of communities). Inside this intersection, social norms that prescribe altruistic rules of conduct might be better enforced through nonmonetary rewards such as social praise, informal recognition, or awards outside of any market exchange.

How does all this new evidence affect Hayek’s model? Since the extended order (type 2) is composed by rules of conduct that have evolved through cultural group selection, the new unexpected kind of altruism might also be a reasonable product of the process for the area that overlaps with the realm of instinctual face-to-face interactions. Both could have coevolved combining genetic and cultural evolution, in which case no change would seem necessary. Since Hayek doesn’t assume self-interest as the main individual motivation inside the open society, his system firmly resists the new shock.

Finally, one possible rationale for the kind of altruistic preferences and behavior with strangers that is crowded out by monetary compensations is virtue signaling (Miller 2019). Individuals can gain reputations for being cooperative and valuable in productive relations with others by engaging in observable and costly prosocial activities (see, for example, Candel-Sánchez and Perote-Peña 2020). This signaling behavior has a double effect: on one hand, it improves welfare by voluntarily contributing to public goods and by providing valuable and credible information about individual productivity; but, on the other hand, it also generates inequality in the long run by rewarding altruistic over nonaltruistic individuals. Virtue signaling can be considered part of the motivation to gain the esteem of others, discussed in the previous section, which Hayek saw as a major determinant of human behavior. Therefore, signals themselves can be considered emergent cultural innovations that make the best use of scattered information, allowing the “moral economy” to be fully incorporated into Hayek’s approach.

Cultural Group Selection

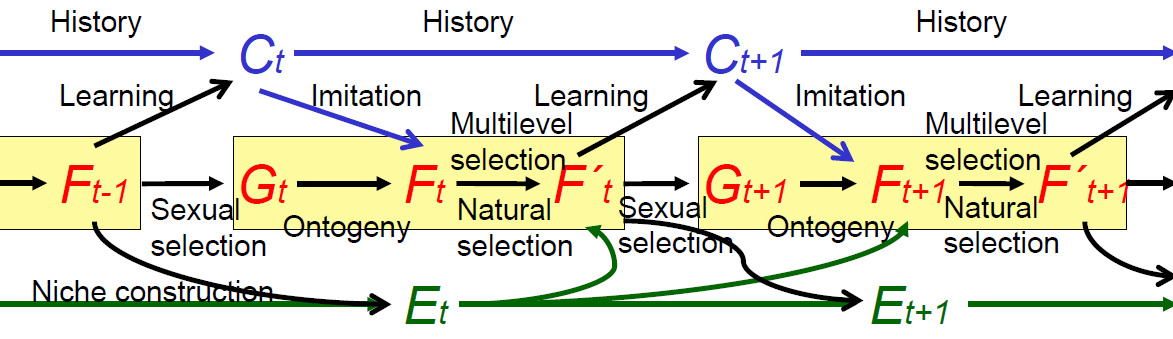

The last theory (or better, group of theories) we consider sprang from the need to find a more convincing explanation of human prosociality toward strangers. But first, it is worth giving a brief historical overview of the major views on the forces that drove human evolution up to the present. Figure 2 depicts the relevant evolutionary processes considered important after Darwinian evolution was generally accepted. Arrows represent the main direct causal influences. As has been the case for all species, human evolution was driven by natural selection exerted on individuals based on their observable characteristics and individual traits (later called “phenotypes” and represented by Ft in the temporal line below). Sexual selection is a particular case of natural selection, while the main determinant of human evolution is the environment, which includes other species and evolves independently. The individuals better adapted to the environment of the period in which they live (represented by Et in the temporal line below) leave more offspring, and their traits will be selected for in the next generation, t+1. Selection at the level of the group also plays a role for humans (recognized by Darwin himself): groups or “tribes” with more altruists willing to sacrifice themselves for the benefit of the group will defeat and overcome other tribes with fewer altruists, but culture (Ct in the upper temporal line of the figures below) was largely viewed as an independent phenomenon or just the collection of the observable phenotypic traits of a particular group of humans individually adapted to the environment in which they live.

This model had many variants—including those that assume the inheritance of acquired traits (Lamarckism)—and was also used to ethically justify interventions to “improve” the gene pool (eugenics) and laissez-faire economic policies (social Darwinism). Later, the genetic basis of inheritance was successfully integrated into the model (genes, or “genotypes,” determine the physical and behavioral traits, or “phenotypes,” in each generation, shown in the figures below as Gt), and after World War II a new vision on evolution emerged in the social sciences seeing culture as the main factor in human evolution (figure 3). The high plasticity of human brains gave rise to a view of the mind as a “blank slate” freely conditioned by culture that explains most of the differences among humans (behaviorism was the dominant school in psychology at the time). Genetic diversity was proved to be low in humans, and culture explained most of the variation in traits, but no particular evolutionary process was supposed to explain cultural changes. Most social scientists assumed that cultural change was an autonomous and historical process somehow unrelated to the human need to adapt to the environment and following mysterious rules of its own.

A new paradigm shift (depicted in figure 4) started in the 1960s when a new generation of biologists (Hamilton, Trivers, and Maynard-Smith, among others) managed to provide an evolutionary rationale for altruistic behavior based purely on genetic evolution. They assumed that natural selection did not take place at the level of individuals or groups but at the level of the gene. Behavior that helps kin at a fitness cost to the actor may evolve because other copies of the same gene benefit from it (kin selection) or when altruistic behavior toward strangers is rewarded later (reciprocal altruism). The new gene-centered view of evolution was popularized by Dawkins (1976) and gave rise to the field of sociobiology when it was applied to humans. Evolutionary psychology emerged as the discipline that inherited this view of human evolution (see Tooby and Cosmides 1992 for a comprehensive view of the paradigm shift). As shown in figure 4, the main process driving human evolution is natural (and sexual) selection acting on genes to develop highly social brains capable of sustaining valuable cultural information to benefit the genes themselves. Culture is seen as either a manifestation of individual-level adaptations or a by-product of them. Miller (2001) even considered it the material product of costly sexual displays in the sexual selection process. At the same time, a new contribution from ecology and evolutionary biology stressed the fact that humans also affect the conditions of their own selection by significantly changing the environment (see Laland, Odling-Smee, and Feldman 2000 and Laland and O’Brien 2011). This new effect assumed a more complex coevolution of genes with part of the environment—the niche construction effect shown in figure 4. Different ecological niches are therefore subject to selection at the same time as the genes that exploit them, enriching the set of relevant influences admitted into the system.

Finally, starting in the late 1970s but gaining prominence in the twenty-first century, a new formulation reintroduced the dynamics of culture as a major causal factor of human evolution. The assumed coevolution of genes with the environment was not considered a sufficient explanation of the extent of human cooperation, and culture was reintroduced as an evolutionary process in its own right, in which “cultural traits” stored in brains are created and transmitted through learning and imitation from the previous generation, giving rise to new forms of cooperation, knowledge, behavior, tools, and adaptation to the environment, and even affecting genes. Since this process of selection and inheritance of cultural traits differs from that which operates on genes, human evolution is better explained as a coevolutionary process of culture and genes (and the environment). In fact, culture could also be considered the evolutionary niche characteristic of humans or the social environment itself. Models like those of Lumsden and Wilson (1981) and Boyd and Richerson (1985) inspired the gene–culture coevolution theory (or dual inheritance theory) that—when combined with a multilevel selection theory that puts together selection processes at the level of the individuals and at the level of the group—is now called cultural group selection.

Group selection enjoyed a revival when its main proponent, evolutionary biologist D. S. Wilson, enrolled the father of sociobiology, E. O. Wilson, on his side and translated traditional kin selection models to analogous versions that combine a degree of selection between individuals (that work against altruistic traits) and a degree of selection between groups (promoting altruistic traits), called multilevel selection (see Sober and Wilson 1998). Although this new approach can illuminate the evolution of intensely group-selected eusocial insects (ants and bees), it can hardly explain the genetic evolution of altruism in humans, because the amount of variation needed between groups is very unlikely to occur in mammals. Figure 5 depicts the causal effects that are considered within these models.

Hayek’s view of social evolution as summarized in section 1 already incorporated all features of the recent cultural group selection models just commented on (those in figure 5) and did it at a time (the late 1960s) when the mainstream vision was shifting from the one depicted in figure 3 to that in figure 4. It has been argued (Birner 2009) that Hayek’s group selection theory influenced Karl Popper’s theory of ecological niches, another outstanding contribution to the topic. Hayek’s pioneering contribution was already noticed by authors like Steele (1987),[3] who criticized Hayek’s approach to group selection on grounds already used by sociobiology (figure 4) and who proposed an alternative “memetic” approach—more in line with classical liberal authors like Hume, Ferguson, and Menger—in which the individual selection of useful cultural variants is more important than group selection, although the adoption process might not be fully rationally planned. A more positive view of Hayekian cultural group selection was defended by Zywicki (2000, 2005) following the increase in popularity of group selection among evolutionary biologists and anthropologists that crystallized after Sober and Wilson (1998). More recently, Stone (2010) identified ten propositions that summarize Hayek’s cultural group selection view and discussed their plausibility in the light of the more recent proponents of the gene–culture coevolution theory presented above when explaining figure 5, finding them remarkably backed by both the theoretical and empirical advances at that time. Since this work can also be considered a vindication of Hayek’s cultural group selection ideas in relation to more recent findings from other disciplines, I should provide my own assessment and address the main points of criticism of the authors mentioned above. Steele (1987), in particular, identifies as a major weakness of Hayek’s group selection theory the lack of detail about the specific mechanism by which a group displaces another. Hayek explicitly admitted cultural imitation, special influence of some individuals, warfare and extinction of less adapted groups, and differential individual and group reproduction as potential mechanisms leading to the same result. Moreover, Steele’s criticism could be overstated since the current evolutionary models grouped in figure 5 under the new cultural evolution paradigm also admit all these possibilities, although some might be more relevant in some domains, contexts, places, or historical periods than others, and all of them might lead to fitness benefits for all members in the group (mutualistic behavior due to enhanced cooperation with better social norms), for only some (elites or the group of “punishers” in charge of enforcing the social norm), or even for none of them (i.e., when the adoption of the norm via imitation leads to worse genetic fitness outcomes for individuals in the coevolutionary process or when warfare is very costly).

Two important points should be taken into account to understand this indeterminacy of the specific mechanism underlying the group selection process. First, the unit of selection problem: although multilevel selection admits that the two forces of individual and group selection operate at the same time (and oppose each other when explaining cooperation, as briefly explained above), what are really selected are either the genes inside individuals (in the case of genetic multilevel selection) or the cultural traits (or “memes,” in the case of cultural multilevel selection). The multilevel selection process can always be translated into a single evolutionary process with a single unit of selection at two different levels (that can sometimes be studied sequentially). Individuals and groups are just carriers of different distributions of genes or memes affecting their relative reproduction rates. At a deeper level, a cultural evolution process does not need to be very specific on the selective forces at work on rules of conduct or social norms, and the combination of them might change with time. Furthermore, the very concept of a group was endogenously defined by D. S. Wilson as the set of individuals benefitting from a gene or trait at the same time in a particular evolutionary context. These are not necessarily identical with observable “ecological groups” containing individuals living in close proximity. An evolutionary niche is defined in the same way (see Trappes 2021). In my opinion, accepting this endogenous definition of groups amounts to making the forces of group selection relevant a priori and not vulnerable to experimental falsification, so I find it scientifically dubious and even unacceptable, but this nevertheless adds to the indeterminacy of the definition of the relevant groups involved in the evolutionary process.

Finally and more importantly, there is strong experimental evidence confirming all the processes considered by Hayek to have been important in the evolution of human cooperation, and in fact there are reasons to argue that it was their combination at different stages of human evolution that was needed to explain human cooperation.

Numerous experiments (such as the public-good game experiments in Fehr and Gächter 2002) pointed to the importance of the universality of the altruistic punishment propensity, ethnocentrism (psychological bias favoring group members over outsiders), blind imitation, and social conformity in driving human cooperation even at a genetic level. Altruistic punishment (the propensity to punish free riders or norm violators at a fitness cost to the law enforcer), once evolved to a critical mass in a particular group, can serve to enforce any arbitrary social norm or cultural trait (Boyd and Richerson 1992). But some social norms, once universally enforced in a group, are better adapted to the survival of the group than others. A trial-and-error process in group competition might benefit the reproduction of the groups with more cohesive or effective social norms (again, the conscious rationality of the norms is not needed and might be present or absent, as Hayek assumed). The problem with altruistic punishment is that this additional prosocial behavior cannot evolve by individual selection either, because punishment constitutes in itself a new altruistic act to be explained (gossip and damage to reputations included). Punishing becomes an autonomous process only when a sufficient number of punishers are available to share the total cost of punishing free riders. A way out of this problem is to use gene–culture coevolution models (the most successful versions were developed in Boyd and Richerson 1985, 2005), but at the end of the day these models rely on some additional form of genetic or cultural selection at the level of the group (this is backed by evidence for ethnocentric preferences). Group selection by warfare and group replacement and extinction is necessary for the genetic evolution of altruistic punishment itself (and again, there is evidence of its importance in our ancestral environment and for traditional hunter-gatherer societies in the anthropological record). But again, group selection is unlikely to work for humans, because in ancestral conditions the absorption of defeated groups and incest avoidance involve the surveillance of the genes that work against sacrificing oneself for the benefit of the group and favor individual selection of free riders against the group selection of ethnocentric altruists.

The theoretical problem can be solved by increasing the variance of traits between groups by adding the third ingredient to the recipe: cultural evolution through conformity (imitation of the majority) could increase both the variation between groups and the number of punishers (see, for instance, Bowles and Gintis 2011). The genetic evolution of true altruism in humans therefore seems to require that cultural evolution by conformity has evolved previously. New evidence from evolutionary anthropology points to a long history of both genetic and cultural coevolution in humans. For instance, genes that allow for processing lactose in adults have evolved in cultures that depend on cattle and sheep. Our vocal tracts, some perceptual systems, and our teeth and gastrointestinal apparatus have also evolved to make the most of cultural innovations like language and fire. Furthermore, our problem-solving abilities have been overestimated: even the construction of supposedly simple technologies like bows and huts require complex sequences of steps that nobody could have developed from scratch (Henrich 2016), so technologies involve rules of conduct that must be learned by imitating others. This is a new and unexpected victory for Hayek that confirms the limits of type 3 rationality and strengthens the power of cultural evolution via imitation alone, but he is rarely cited in this literature as a pioneer (neither Henrich 2016 nor Boyd 2018 cite Hayek).

To sum up, at the moment there seems to be an implicit confluence between some group selection ideas (defended by biologists D. S. Wilson, E. O. Wilson, and Peter Turchin), economic and game theory models (like those of Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis), and the new mainstream in evolutionary anthropology (based on work by Robert Boyd, Peter Richerson, and Joseph Henrich), forming a unified theory of culture–gene coevolutionary group selection. Richerson et al. (2016) put together the qualitative and quantitative evidence supporting the new framework to account for human cooperation. Some authors even claim that such a theory could unify all social sciences (Mesoudi 2011; Gintis 2009; Richerson et al. 2016). Again, Hayek proposed cultural group selection in his model for the evolution of type 2 rules of conduct in the late 1970s when it had been widely discredited, so this new scientific shift ultimately supports Hayek’s view. Finally, another idea defended by Hayek and emerging in the new theory is summarized by Turchin (2016, 236): “To work effectively, good institutions should be buttressed by matching moral values. An inclination to help relatives and friends is a prosocial value appropriate for small-scale societies. But in large-scale societies, it needs to be subordinated to a disposition against nepotism and cronyism. So, in reality, it was the coevolution of institutions and values that made cooperation in ultrasocieties possible. And a unified theory must account for both.”

Normative Implications of Cultural Group Selection

What Hayek probably could never have predicted are the ethical and policy implications stated by the current scientific supporters of the new theory. Let us start the discussion by saying that the cultural evolution theories sketched above (Hayek’s version included, as stated in Nadeau 2016) are supposed to be descriptive of the actual and past processes of change and emergence of social norms and cultural traits and should not be viewed as normative theories.[4] But the narratives implied by the theories invariably carry unambiguous messages about what count as good or bad rules of conduct or institutions, and these messages are sometimes made explicit by the authors themselves.

Let us start with the ethical conclusions that can be derived from assuming that humans have been culturally and genetically group selected. Here are a few relevant quotations: “Thus, cultural evolution initiated a process of self-domestication, driving genetic evolution to make us prosocial, docile, rule followers who expect a world governed by social norms monitored and enforced by communities” (Henrich 2016, 5). “An unavoidable and perpetual war exists between honor, virtue, and duty, the products of group selection, on one side, and selfishness, cowardice, and hypocrisy, the products of individual selection, on the other side” (E. O. Wilson 2012, 56). And, in reference to bees, D. S. Wilson (2019, 224) says that “colony-level selection is the invisible hand that promotes the individual-level behaviors that benefit the common good rather than the much larger set of behaviors that would harm the common good.”

In my opinion, some versions of the idea look undoubtedly messianic in nature and are possibly influenced by the green philosophy and some quasi-religious environmentalist movements. D. S. Wilson (2019, chap. 4) goes so far as defining the concept of “good/right” with whatever benefits the group and “bad/wrong” with whatever is self-interested. He also raises the idea of extending group selection to the whole planet (something that the group selection theory cannot support) to encompass a “superorganism.”[5] Similar ideas can be found in E. O. Wilson (2012) and Nowak and Highfield (2011). This new revival of scientific historicism sees our future as a superorganism in which all individuals are entirely subordinate to the goals of the common good, defined as whatever is needed for the group to succeed, at a scale that dwarfs previous attempts by Plato’s Republic, Hobbes, and Rousseau—that even Marx’s chosen people (the proletariat) would have never imagined.

The supporters of this new, ambitious, and science-based project of evolutionary theory feel released from the mantra of undirected evolution that was a hallmark of Darwinism: since culture is accumulative, it evolves progressively, and once we consciously know the laws that govern the system (group selection), we will be able to make informed predictions. Peter Turchin is collecting historical information to test the theory in his “Seshat: Global History Databank” project, a goal that Karl Popper would most likely have considered impossible. It is unclear whether Hayek would have agreed with some kind of predictability of the system, since while emergent properties cannot be ascertained from knowledge of individual behavior, understanding the higher level rules of the system is something different.

Regarding the morality of altruistic individuals sacrificing themselves for the survival and benefit of the group under intense group selection, it can be argued that this is as costly and wasteful as a purely selfish morality that avoids contributing to public goods that benefit others. Competition against other groups can be considered a contest for positional goods or an arms race at the group level, where investing in survival and supremacy requires heavy investments of resources in warfare, deterrence, internal indoctrination, and punishing behavior, all for the purpose of destroying the opportunities of rival groups that are doing the same. From a utilitarian perspective, what seems to be a public or common good at the individual level (altruistic sacrifice for the group benefits all members in the group by improving its chances of survival and reproduction against rival groups) is nevertheless a public bad at the global level. All individuals would be better off in terms of absolute adaptive fitness and welfare if this kind of group competition was abolished and altruism was limited to real public goods. Hayek’s understanding of the extended order implies this universalistic and libertarian kind of group selection in which human cooperation and peaceful trade are not limited by frontiers and ethnicities and competition between groups creates value for everyone with little waste. Adopters of free market capitalist institutions form an endogenous cultural group of presumably final winners that elevates group competition to the most cooperative and least wasteful level in a libertarian society. A libertarian free market global society as conceived by Hayek therefore seems to be a much more convincing stable evolutionary equilibrium of the cultural group selection process than a “technosocialist” global utopia (see Boettke and Candela 2023 and W. P. Cockshott and Cottrell 1993; W. Cockshott 1997 for discussions on this possibility), where economic decisions are implemented by an omnipotent and paternalistic social planner or “superorganism” that accumulates and processes all relevant information and coercively internalizes all externalities for the inferred common good.[6]

Let us move now to the specific policies proposed by the scientists of the new theory. Most of them are associates of or contributors to the Evolution Institute, a think tank created by D. S. Wilson to advance and test policies from the new theory and that also publishes the magazine This View of Life and the digital publication Evonomics. The authors themselves refer to a toolbox for designing new organizations, policies, and institutions. Henrich (2016, 331) argues, “Humans are bad at intentionally designing effective institutions and organizations, though I’m hoping that as we get deeper insights into human nature and cultural evolution this can improve. Until then, we should take a page from cultural evolution’s playbook and design ‘variation and selection systems’ that will allow alternative institutions or organizational forms to compete. We can dump the losers, keep the winners, and hopefully gain some general insights during the process.” And D. S. Wilson (2019, 273–74) says that

clearly, more is needed for human groups of all sorts to adapt to change at the speed and scale that is required to solve the myriad problems of our age. The first step is to adopt the right theory. . . . We are like an engineer who is trying to build something using the wrong blueprint. It will never work, no matter how smart we are or how hard we try. The right theory is based on the cultural evolution of complex systems. It notes that complex systems cannot be optimized by separately optimizing their parts. We must have in mind the performance of whole systems, which is the target of selection, and improve performance with a process of variation and selection of best practices. This is likely to work much better than laissez-faire or centralized planning.

These authors seem to support intervention policies that make use of evolutionary processes of selection under fixed conditions or controlled rules that set the communal goal desired by the social planner as the object of competition. For example, D. S. Wilson (2016, chap. 6) proposes applying Elinor Ostrom’s Core Design Principles (1990) to tackle not only common resource problems but any social problem at any scale (see also D. S. Wilson, Ostrom, and Cox 2013). The outcomes and solutions obtained might not be predictable, but the evolutionary process guarantees that they are at least aligned with the benefit of the group.

This procedural approach to social engineering can be seen as a third way between, on one hand, a centrally planned agency using disperse information to allocate resources to maximize the achievement of some notion of the common good (relying fully on human rationality) and, on the other, letting group selection in the actual world, as it is now under laissez-faire, decide which institutions and rules of conduct will win the ongoing competition (relying fully on group selection). They propose new innovative institutions (or more likely the government) to undertake a new type of social engineering that makes use of artificial selection of ideas, rules of conduct, and economic plans by means of designing a common ground of simulated competition between institutions under fixed legal rules that allow for the selection of those that perform best in a contest for the benefit of all. But that is almost the description of the actual working of competitive markets in a free economy with private property under the rule of law, the organization of scientific institutions in the “market for ideas,” or the evolution of the common law! And these are some of the examples that Hayek used when explaining the operation of the extended order under group selection conditions. The reason why so many academics in evolutionary science do not seem to realize this, in my opinion, has to do partly with anticapitalist prejudices and partly with a misunderstanding of the paradox of Adam Smith’s invisible hand by biologists and other social scientists. In the natural world, selfish competition does not produce the best result for the group, because there is no labor specialization determining the production possibilities, very little diversity of individual interests, preferences, and skills, and few constraints that limit the evolution of aggression, predation, and parasitism. Most of the useful knowledge in animal societies is already embodied in instincts and inherited genetically. It is not produced, revealed, and distributed, although biological markets sometimes emerge spontaneously under certain conditions (Noë, van Hooff, and Hammerstein 2001),[7] such as in the trading of chemical compounds between plants and some fungi species. By contrast, the economic and social problems humans face are related to the use of knowledge, cooperation, and coordination of behavior on a large scale (as noted in Hayek 1945). Following private interests does indeed result in a benefit for all under evolved rules that combine property rights and peaceful trade on a voluntary basis. Only eusocial insects (ants, bees, and termites) have achieved levels of organized complexity similar to those of humans, following a different, noncultural evolutionary path that combines group selection with a very unusual genetic inheritance system that favors kin selection. It is very surprising that the scientists who propose institutions of regulated competition as social learning mechanisms cannot admit that these systems have already emerged as spontaneous evolutionary outcomes in the modern world and that there is no need to reinvent them: the deep, implicit, and complex knowledge embodied in the systems of competition and cooperation emerged without a rational, enlightened decision-maker.

Another weakness of the suggested alternative to “simulated competition” between institutions selected for the common good, when compared with Hayek’s view of competition in free markets under predictable rules, lies in the difficulty of defining a priori the common good in the first place. As Steffen Roth (2024, 6) has argued when describing the quasi-totalitarian political implications of thinking about Earth as a holistic entity in his metaphor of “Spaceship Earth,” the “capture of the regulator” and crony capitalism are the likely outcomes of simulated competition under a top-down definition of social objectives. This danger is avoided by letting all individuals in a free society jointly define the objectives of the economic system by credibly revealing their preferences in markets so that the price system reflects priorities in the allocation of resources a posteriori—what is implicit in Hayek’s own conception of the cultural group selection process.

Concluding Remarks

Hayek’s societal evolution theory, developed in the 1970s and 1980s against the mainstream view at the time, has turned out to be much more compatible with scientific evidence in the twenty-first century than competing theories, and although he did not develop a quantitative testable model, he certainly deserves to be considered a pioneer in the field. Nevertheless, the scientists who lead this highly interdisciplinary field rarely cite Hayek and those who acknowledge his seminal contributions, such as D. S. Wilson, who used to take a hostile position to Hayek’s support of laissez-faire economic policies, confidence in free markets, and libertarian ideology (see D. S. Wilson 2015, 2016, 2017). It is surprising that these authors apparently do not consider the economic system of free markets based on property rights under the rule of law to be the evolved institutional framework that they have predicted as the likely outcome of cultural group selection. Regarding the specific mechanism of the cultural group selection process, it seems that the mixture of ideas and rules of conduct adopted by conformist imitation, social pressure (punishers), or intergroup conflict (warfare) are all, as admitted by Hayek, necessary to human evolution. But the current models are still highly speculative and none of them can give a reasonable account of the evolution of the most characteristic and complex cultural niche of humans—language—so it is fair to say that we still do not have a final answer concerning the details of the cultural evolution process. Finally, I hope to have shown that accepting Hayek’s social evolution model obliges his followers to seriously consider some policy recommendations, such as Frank’s tax, to alleviate the damaging arms race of positional consumption—or to admit that economic incentives sometimes backfire, as discussed in sections 2 and 3. Behavioral economists should also consider the coevolution of virtue signaling and rights—producing novel ideas and disseminating useful knowledge about personal traits—as a likely product of Hayekian cultural group selection. Hayek’s approach not only accommodates the new findings but illuminates their origin and functions better than alternative theories. Furthermore, I have argued that the Hayekian view of prices as signals that aggregate widely dispersed information and markets as behavior coordination devices fully embodies the open evolutionary mechanisms that scientists in the new field of cultural evolution are currently proposing. Right now, paradoxically, the similarity of the theoretical approaches to social evolution of Hayek and the evolutionary scientists within the new cultural evolution paradigm does not translate to similar predictions or concerns in political philosophy. This raises a somewhat artificial barrier between libertarian adherents to Hayek’s ideas and evolutionary scientists.

All figures have been elaborated by the author.

I wish to thank an anonymous referee for making this point and calling my attention to Tarde’s “The Laws of Imitation,” which also shows in great detail that the selection of imitative structures usually involves little conscious agency, as Hayek emphasized much later.

I wish to thank an anonymous referee for letting me know about the work of this author and others in the same strand of literature.

The naturalistic fallacy (Hume’s law) is the tendency to infer normative propositions from factual statements.

The idea of reuniting with the absolute comes from a very old tradition in the West, with different versions from Neoplatonism and Gnosticism in antiquity to Teilhard de Chardin’s “omega point” and the end of history after a “struggle for existence” in different versions of Marxism and national socialism. The totalitarian associations of this idea are apparent.

There have been attempts to implement centrally coordinated social engineering and economic planning based on data, such as cybernetics expert Anthony Stafford Beer’s Project Cybersyn in Salvador Allende’s Chile.

See, for instance, Ronald Noë’s personal site: https://sites.google.com/site/ronaldnoe/markets-main/BM-grooming-primates.